In winter, when the trees are bare and fields are blanketed with snow, I always anticipate seeing eagles, hawks, and owls. My eyes continually scan the surrounding area for large birds this time of year. In my opinion, one of the most majestic and striking winter birds in Michigan is the snowy owl. I was driving on Monroe Road the first time I spotted the large white owl. It was perched on a telephone pole, motionless, looking for prey in the open fields. Pulling into a nearby driveway to take photos, I slowly stepped out of my car. Suddenly, the owl’s head rotated and I was met with two large, piercing yellow eyes staring right at me. I froze. I did not want to disturb this beautiful, powerful and intimidating predator. I kept a respectable distance while I snapped a few photos before getting back into my car and giving the bird space to continue hunting. Many winter days I have passed the owl on the same pole, and it always fills me with excitement and awe. This year, I did not see the owl until late January, but it was on that same pole once again.

The snowy owl is the largest owl in Michigan and the only owl that is primarily active during the day. Owls, like hawks and eagles, are raptors. They use sharp talons and curved bills to hunt, kill, and eat other animals. What makes owls unique among raptors are their huge heads, stocky bodies, and a reversible toe that can point forward or backward. Also, their eyes face forward, like humans do. Owls are mainly active at night, not the daytime, with the exception of the snowy owl.

Owls have many interesting adaptations to help them hunt. To locate prey buried in the snow, owls have sensitive and powerful hearing. A disc of facial feathers helps direct sound to their ears to pinpoint the location of prey. You can get an idea of this acoustic effect by cupping your hands behind your ears. The ears of an owl are unique in that they are asymmetrical, one ear is slightly higher than the other to help determine the direction of sounds. In flight, owls are incredibly silent. Specially adapted feathers, with serrated edges and hollow feather shafts break up the air turbulence into small currents, reducing sound. Owls also have special eyes adapted for low-light environments. Instead of spherical eyeballs, owls have eye tubes like binoculars that go far back into their skulls. Their eyes are fixed in place, so unlike humans, they cannot move their eyes peripherally. This is why owls must rotate their heads up to 270 degrees to look around.

Owls spend much of their waking time hunting for food. Most owls are carnivores, hunting small rodents, voles, frogs, snakes, fish, mice, rabbits, birds, squirrels, and other animals. Owls even hunt other owls! In Michigan, snowy owls tend to feed on rodents and waterfowl. In some cases, they have been known to take larger prey including birds as big as geese! Owls often hide their food in a behavior called “caching”. The owls will stuff the food into a hiding spot like holes in trees, forks of tree branches, or behind rocks. They do this to stock up while hunting is good and will return to the prey in a day or two.

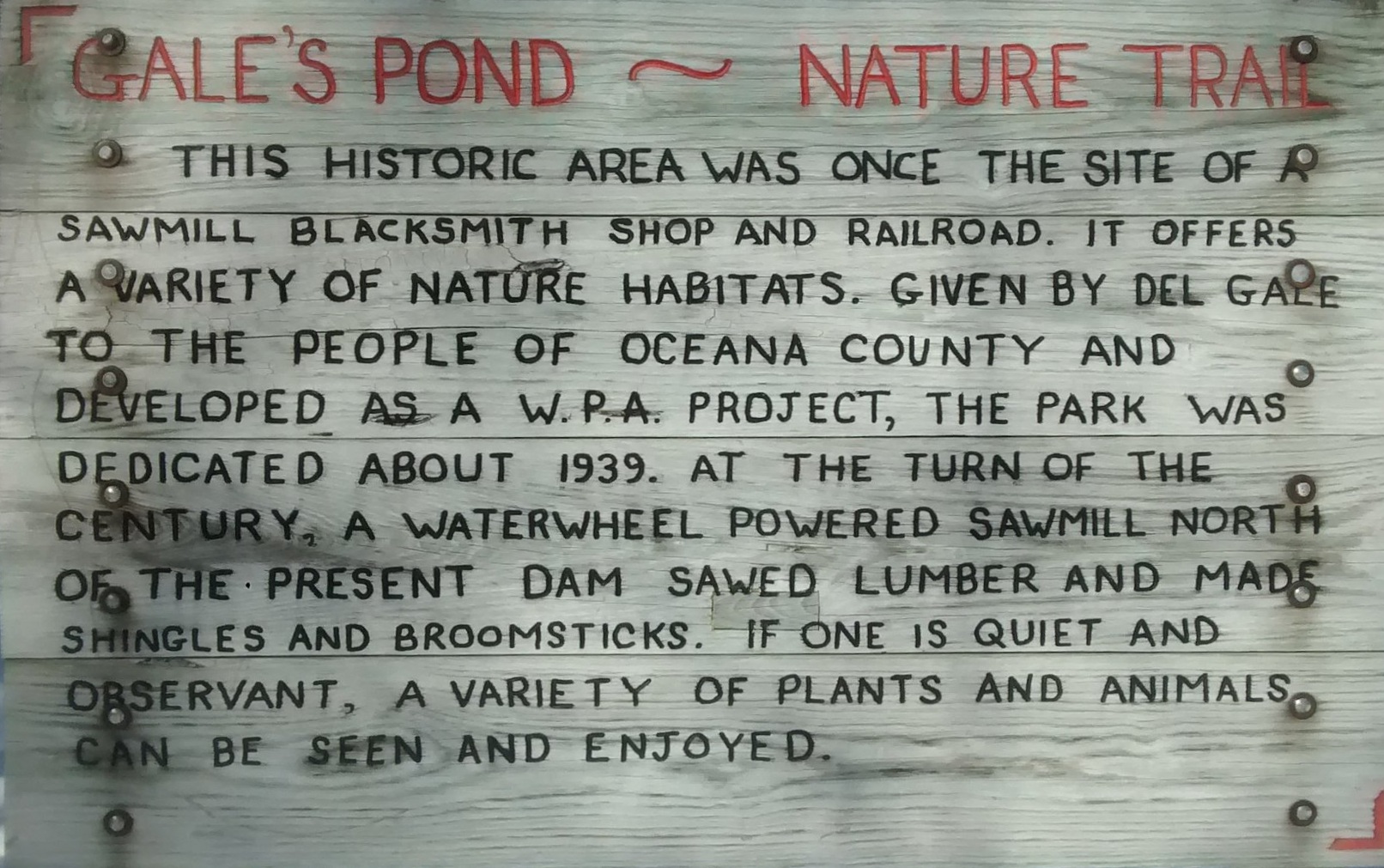

In summer, snowy owls nest and breed in the Arctic in northern Alaska, Canada and Eurasia. However, a strong dependence on their prey species results in a highly nomadic behavior following fluctuations in prey population. In years with reduced rodent populations, snowy owls are forced to breed in more southerly locations, and in some instances will forgo nesting all together when resources are scarce. In winter, southern migration can vary from year to year, presumably related to populations of prey in the north. During some years, large populations migrate south of the Canadian border, often spotted in open country including prairies, farmland, beaches and large airports. The Great Lakes attract snowy owls most years, and they are occasionally spotted in Oceana County. Last year, local birders reported at least three different snowy owls in the county. The BioPure Wastewater Facility in Hart is a good place to catch a glimpse of this beautiful bird. They are often seen sitting on telephone poles or fenceposts.

If you are lucky enough to catch a glimpse of this marvelous owl, you will understand why snowy owl sightings can cause a local stir and attract media attention. The snowy owl holds a place in folklore around the world. In Romanian folklore it is said that if a sinner dies repentant, his soul will fly to heaven as a Snowy owl. In China, the snowy owl is called ’bai ye maozi’ (white night cat).

To learn more about the owls present in Oceana County, consider attending our annual Owl Prowl event at the Otto Nature Preserve on February 27. While we cannot guarantee hearing an owl, we enjoy sharing stories and knowledge about owls while taking a slow walk through the forest at night. Please visit our website event page here or contact the office for more information and to sign up for the Owl Prowl.